In a Rolling Stone interview early in her career, Taylor Swift admitted, “I think I have a big fear of things spiraling out of control.” And that was before this past November’s Ticketmaster meltdown. Ted Kooser, a former Poet Laureate of the United States, inventively describes something we’ve all owned at some point in our schooling in his poem, “A Spiral Notebook”:

The bright wire rolls like a porpoise

in and out of the calm blue sea

of the cover. . .

. . . with its

college-ruled lines and its cover

that states in emphatic white letters,

5 SUBJECT NOTEBOOK.

These two connotative meanings are the ones our minds race toward when hearing the word “spiral,” but there is another meaning that encompasses more than famous pop stars and poets. Spiraling, in the educational sense, is a term coined by Jerome Bruner, a Harvard-trained educational psychologist. It is an instructional approach commonly used in many classrooms worldwide, including those at PA Virtual.

And if the word, Chunk, makes you think of your favorite character from Goonies, you’ll be surprised to know that it is also an instructional approach PA Virtual teachers use to deliver content to students in a way that is more manageable and meaningful.

Today’s blog will explore both approaches and how they make content across the curriculum more accessible to various learning styles and levels.

Spiraling

Bruner’s spiraling theory is simple: “a spiral upward from basic to advanced concepts, with topics revisited at increasing levels of complexity as the spiral loops around” (Ireland & Mouthann, 2020). Just think about that blue spiral notebook, right?

In the classroom, spiraling allows students to achieve a sophisticated level of knowledge by starting with basic concepts and moving into advanced concepts. An instructional example would be the process through which students read texts and identify themes. Whether it’s Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? or The Scarlet Letter, students read (or listen) for meaning and determine the “central message,” “lesson,” “central idea,” or, ultimately, “theme.” In action, you can see this progression through the PA Core Standards curricular sequencing.

- Grade 1: Retell stories, including key details, and demonstrate understanding of their central message or lesson.

- Grade 4: Determine a theme of a text from details in the text; summarize the text.

- Grade 7: Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text.

- Grade 11-12: Determine and analyze the relationship between two or more themes or central ideas of a text, including the development and interaction of the themes; provide an objective summary of the text.

Teachers first introduce the notion of theme as “central message” or “lesson,” terms accessible to first-grade students. By their junior and senior years, students are still building on the idea of a “lesson,” but doing so in an advanced manner. Moving beyond identifying one lesson from a story, students are now analyzing multiple themes. Through this spiraling curriculum that provides- developmentally- and intellectually-appropriate instruction, students acquire the skills for the rigors of each new grade level and the critical thinking required for life beyond high school.

Benefits of Spiraling

If you think about real life, “spiraling” is how we all learn. It’s natural, it’s incremental, and it allows us to make seemingly complex activities appear simple and become second nature. Ask any ballerina how she’s able to pirouette without a problem or how a crew team can rapidly row in repetition. Spiraling is all about reinforcing basic concepts over and over, revisiting them in incrementally more complex ways, and keeping these foundational skills fresh in students' minds. Teachers then have more opportunities to assess student’s progress and, perhaps more importantly, provide early intervention if students struggle with foundational concepts. These opportunities abound in a data-driven school like PA Virtual, where teachers can quickly intervene with students who are not achieving benchmark performance. Students and learning coaches can better understand the reasoning behind teacher-requested interventions and more fully appreciate the need to master academic content.

Chunking

Chunking, too, is a relatively simple idea. Take a break from reading this blog and say your phone number out loud. How did you say it? Was it ten numbers rattled off with no separation? No, I’m pretty sure you chunked it by three numbers, and then three more, and then four. What about your social security number? Don’t say it aloud, but how did you chunk those numbers? Again, you separated the numbers into manageable chunks and were able to recall them without any issues. Being able to recite your phone number or SSN isn’t going to win you any academic fame and glory. Still, chunking is a deceptively simple instructional method that allows students access to and, eventually, mastery of a difficult concept.

Before jumping into classroom application, there’s a great example of the teach-by-chunking method from a memorable 80s movie. If you guessed The Karate Kid, you’re right. Mr. Miyagi didn’t throw Daniel into a fight with the Cobra Kai bullies immediately. What made Mr. Miyagi an effective teacher was not his combined knowledge of karate; what made him effective was the ability to chunk all the needed skills Daniel would need to combine later. He didn’t overwhelm the unpracticed student at the start of the lesson; he thought of the end goal and linked together chunks that led to a holistic understanding of karate.

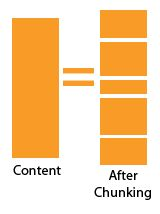

In the classroom, the accompanying graphic reflects the power of chunking content. It makes large amounts of content manageable, allowing students to understand a daunting piece of content more thoroughly. Students benefit significantly from the bite-size chunks, whether a mathematical concept, a historical event, or the writing process.

Benefits of Chunking

Although “chunking” may be a recent term in classroom instruction, authors have used it for hundreds of years to make their writing more accessible. Do you remember struggling with Shakespeare when you were in high school? The Bard of Avon used chunking when writing his Elizabethan sonnets. Sonnet 18’s “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” is a great rhetorical question, but if reading in succession the other 13 lines of the sonnet leaves you cross-eyed and confused, no worries, Shakespeare accounted for this. His 14-line sonnet is three quatrains (four lines each) and a couplet (two lines). Read the first four lines, pause, think, regroup, and then move on to the following quatrain. Then read the third quatrain, and you only have the couplet left. The best news is that the final two lines (the couplet) often elucidate the theme, summarizes the thoughts, or provide a way to end the poetic musings satisfactorily. Shakespeare’s sonnets are chunking at their best, and the Poetry Foundation says it best: “This different sonnet structure allows for more space to be devoted to the buildup of a subject or problem.” That’s the exact opportunity teachers give students when chunking a complex or problematic text. Students can benefit from this approach regardless of their reading ability, and they will have a more in-depth understanding of how the skills relate to the overall objective.

With PA Virtual’s asynchronous course offerings, chunking becomes an even more crucial instructional approach. Teachers deliver content in “chunks” that deliberately sequence the learning process, and Learning Coaches can help their children more effectively in day-to-day learning. Every parent has struggled with schoolwork. With the effective use of chunking, teachers allow parents and students to realize their potential as active participants in PA Virtual’s academic programming.

Spiraling and chunking are different approaches to instruction, but both value students’ goal of content mastery. Through these approaches, daunting and formidable academic material across the curriculum becomes within reach for students. Because of this, spiraling and chunking help promote and sustain the love of learning!

Comments